Post-Holocene Open Food-Systems

A critical visual exploration into the future of a post-Holocene climatarian diet.

Switzerland 2043

Pascal Wicht

In the wake of devastating climate disasters, geopolitical instability, and societal upheaval, the world of 2043 is transformed.

This project invites us to adopt an unconventional mindset, one that challenges us to welcome and embrace the unfamiliar. If the future food system we envision doesn’t appear strange, divergent, or even alien compared to our current framework, it’s a sign that we are still tethered to old paradigms. To truly innovate, we must unlearn the past, leave room for the new and boldly step into the unexplored.

A future of food scenario exploring the a post-holocene diet using Midjourney.

This speculative and generative experiment explores a future scenario of a society that has relocalized and is regenerating most of its food systems, drawing from a blend of traditional practices and cutting-edge innovations. It dives into the rise of regenerative agriculture and the resurgence of local bio-economies, underpinned by a radical shift towards vegetarian, vegan, mushroom and insect-based diets.

Amidst the haunting echo of famines and food shocks that have shaken even the affluent nations in the global north, this narrative imagined in Switzerland presents a stimulating counterpoint. It invites the rise of a gastronomic revolution fuelled not by abundance and elitism but by necessity, creativity and resilience.

Throughout history our diets have been dictated by the constraints of our climate niche. As we leave this niche we’re confronted with various challenges and opportunities for innovation

Imagination is a powerful tool that enables us to envision the future. But when it comes to imagining something entirely new, it can be beneficial to ground our imaginings in the familiar, a point of reference from the present that can help guide us into the uncharted territories of the future.

Bread, a ubiquitous and time-honored staple of human diets worldwide, is such an anchoring point. It serves as a universal symbol of sustenance, community, and tradition. By using bread as a starting point, we can bridge the gap between the known and the unknown, between the comfort of the present and the mystery of the future.

In this scenario, I invite us to peer twenty years into the future and consider the shape and structure of a world where market-based solutions no longer dictate the course of societal development. What would it mean to transition from a model predicated on economic growth and competition, to one that prioritizes the well-being of all living things, rooted in principles of collaboration, sustainability and mutual aid?

Such a vision offers us an opportunity to redefine our relationship with food. If we extricate food production and consumption from the capitalist paradigm, what novel forms might they take? Without the constraints of profitability and market competition, how might we reimagine the systems that bring nourishment from soil to table? Can we envision food not as a commodity, but as a common good, a universal basic service that each member of our global community has a right to access?

In this future, our lakes become communal resources, rich with nutrient-dense algae. Their cultivation and harvest are communal activities, not profit-driven enterprises. Instead of packaged products, we might see food become an open-source solution, adaptable and customizable to individual nutritional needs and culinary tastes.

The Resilient Table tells a tale of food transformed – from a commodity vulnerable to the intensity of a climate anomalies and the rivalries of competing markets to a universal basic service that assures health and fosters creativity. In this narrative, once a symbol of societal division and environmental disregard, the future of food becomes an emblem of resilience and solidarity.

The year is 2043 and the future of food is being rewritten amidst the rubble of a broken food system. However, rooted in resilience, driven by creativity and guided by sustainability, it offers an mysterious glimpse of a future where food, once a symbol of global inequalities and environmental degradation, becomes a beacon of hope and a catalyst for change.

The once fertile landscapes now bear the scars of relentless climate disasters, pandemics and severe food sovereignty shocks. The once predictable seasons are now a chaotic mix of extreme weather events, making growing food a Herculean task. Yet, in every crisis lies the seed of radical change. This crisis has spurred the emergence of novel food systems that combine regenerative bioeconomies with cutting-edge and open technology.

How might we reimagine our relationship with food, shifting from a product packaged for retail to a shared resource grown for communal well-being? How might we design a food system that values democratic governance, ecological stewardship and common-based sharing of practices?

What would our meals, our diets, our packaging look like in a world where access to nourishing, sustainable food is a universal basic service? How might the culinary arts evolve and adapt in this new paradigm?

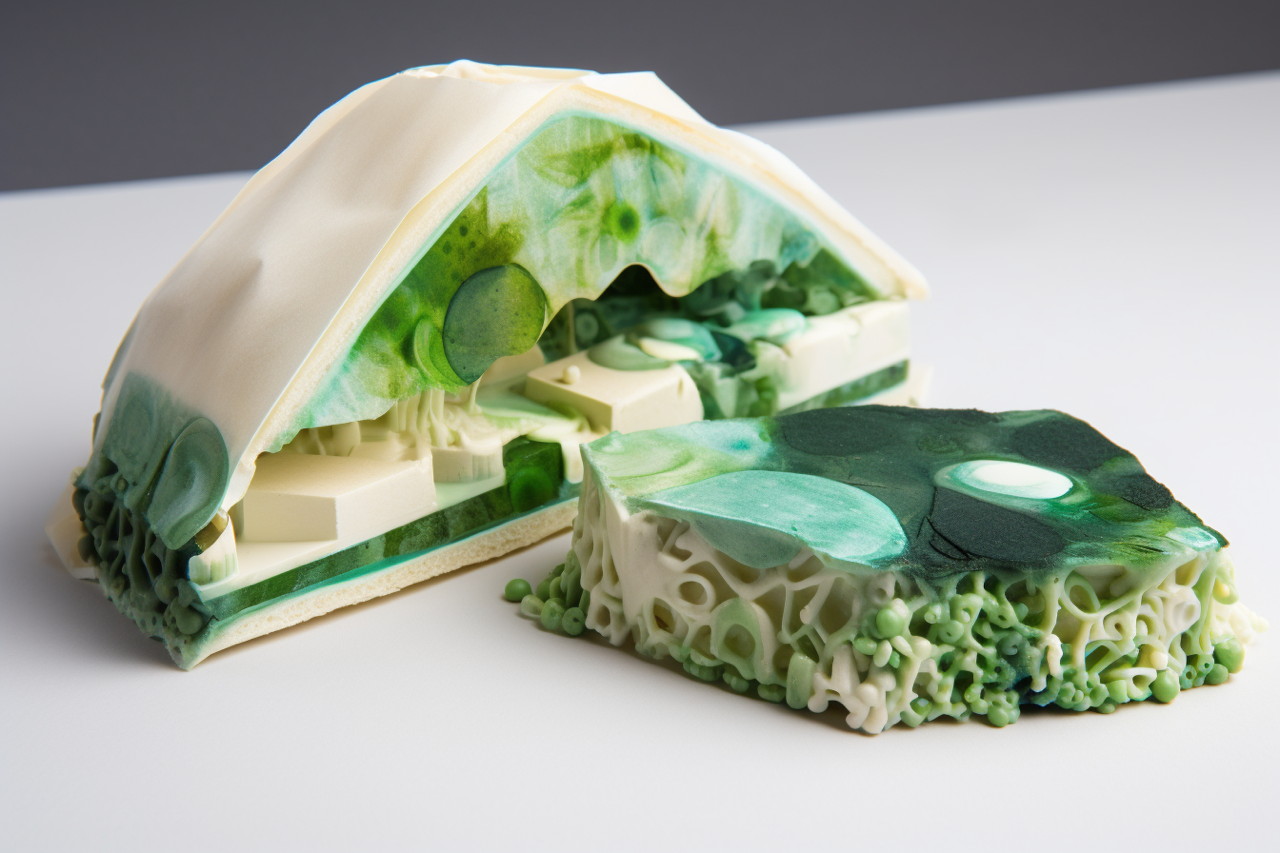

To answer this, in 2043 Switzerland, a regenerated bioeconomy is flourishing, centred on algae and additive manufacturing. Algae farms are proliferating, resilient to extreme weather conditions, and require minimal resources. They produce nutrient-dense biomass as the raw material for solar-powered 3D food printers. These printers can transform this nutrient paste into various textures and shapes, providing nutrition and variety despite the challenging growing conditions.

Meanwhile, food insecurity has become a widespread concern, prompting a re-evaluation of our diets. Vegan and vegetarian diets are increasingly being adopted, not just due to ethical concerns but also due to the practical realities of resource scarcity and volatile global supply chains.

Packaging has also mutated to edible composites and biopolymers, opening up new horizons for manufacturing. Additive technologies also redefine the ability to create new form factors. Health concerns, too, are driving changes in dietary habits.

In this era, food is becoming… strange. Once familiar food items are being replaced by novel, often unconventional ingredients. Mushrooms, for their adaptability and nutritional profile, have become a staple.

Weeds and herbs, previously overlooked, are now appreciated for their resilience and phytonutrient content. Once associated with pollution, algae are recognized for their nutrient density and versatility.

The cornerstone of this transformation lies in the re-emergence and re-invigoration of local food systems. Urban and rural communities have rekindled their symbiotic relationship with the land, intertwining time-honoured agricultural practices with innovative, low-tech solutions inspired by cutting-edge research and open-source collaborations. As a result, the once-clear demarcation between rural and urban landscapes has blurred as every available space—from rooftop gardens in high-rises to automated algae farms have been reclaimed for resilient food production.

At the heart of this metamorphosis, the country’s serene lakes have become the lifeline for sustainable food production and a model of regenerative agriculture. They are now the cradle of a flourishing algae commons.

Algae farming on these lakes is the cornerstone of the regenerative efforts, providing an ideal solution for nutrient production and nature-based carbon capture. These organisms, once overlooked, are now considered a supercrop, not only for their nutritional value but also for their ecological benefits. Fast-growing and adaptive, algae are farmed using minimal resources, without the need for fertile land or synthetic fertilizers.

This practice is driven by principles of biodiversity, soil, lakes and rivers health and carbon sequestration, merging modern scientific knowledge with learnings from indigenous farming methods.

As the algae grow, they absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, thereby actively contributing to climate mitigation. Simultaneously, algae, as a nutrient-dense food source, have become integral to the Swiss diet, providing essential proteins and vitamins.

Alongside insects, algae have emerged as another cornerstone of our food system. Cultivated in vertical farms powered by renewable energy or nutrient-rich water bodies, algae are a robust and resilient source of nutrients, particularly proteins and omega-3 fatty acids.

In the face of an unpredictable and often unstable food production environment, the roles of cooks and chefs have dramatically evolved. They are now more than merely food preparers but agile and resilient food system managers capable of adapting to the ebbs and flows of local food availability. They have transformed into a hybrid of chefs, biologists, and engineers, operating at the intersection of gastronomy, ecology, and technology.

These culinary innovators leverage a range of food production techniques, from traditional farming to additive manufacturing and biotechnology, to maximize the benefits of each. For example, they use 3D food printers to create nutrient-dense meals, leveraging open-source designs that can be adapted to the available ingredients. At the same time, they honour and preserve traditional culinary techniques, recognizing the value of culinary heritage and the sensory pleasure of food.

Common-based manufacturing, in turn, has provided a framework for these tools’ decentralized and collaborative production. Communities across the globe can share, adapt, and improve upon each other’s designs, leading to rapid innovation and the proliferation of locally appropriate solutions. Manufacturers, instead of competing, cooperate within this shared ecosystem of knowledge and resources.

This transformation has been guided by open design principles, which value transparency, inclusivity and collaboration. Under this paradigm, the design process is not confined to a select few but is a collaborative endeavour that invites participation from all. This approach has cultivated a global community of innovators continually pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the kitchen.

In the low-carbon society of 2043, the concept of packaging has been fundamentally reinvented. Inspired by Southeast Asian practices, our society has embraced the potential of seaweed and other organic composites to offer abundant edible packaging solutions. Seaweed farms dot our coastlines, harnessing the power of the sun and sea to produce this versatile material in a carbon-negative process.

This edible packaging eliminates waste and adds nutritional value to the food it encases. It can be consumed with food or composted, contributing to the closed-loop bio-economy. Food is no longer a passive entity designed to fit within the constraints of existing packaging systems. Instead, food and packaging design has become an integrated process, each influencing the other in a co-evolutionary dance.

In some instances, 3D food printers have adapted to directly incorporate this edible packaging into their food items, producing self-contained meals with no external packaging required. For example, a protein-rich insect paste sandwich might be printed within an edible seaweed casing, creating a nutritious and convenient snack that leaves no waste behind.

In other instances, traditional practices are applied to these new materials. For example, once done with banana or lotus leaves, leaf-wrapping now also incorporates large sheets of thin, flexible and edible seaweed composite. These practices have become a form of culinary art, with intricate wrapping patterns contributing to the aesthetic and gastronomic experience of the meal.

In 2043, food has become more than a basic necessity—it is a universal right, a catalyst for community and a canvas for innovation. A universal basic food service, premised on resilient and regenerative local food systems, guarantees that no citizen goes hungry.

Access to nutritious food is no longer a matter of personal wealth but a societal commitment. The service ensures that every citizen receives a diverse array of locally sourced food items, from vegetables and grains to insect-based proteins and algae-derived nutrients.

This diet, rich in micronutrients and low in processed ingredients, has not only helped survive in times of extreme droughts and global supply chain shocks they have also significantly improved public health.

End of Part One

All images are generated using the Midjourney Ai. No image has been retouched and are presented uncropped.

Work is published under a Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)