The challenge of imagining life beyond capitalism

The end of the world has been a popular theme in literature, but have you considered the end of capitalism? Fredric Jameson argues that imagining a world without capitalism is harder than imagining the end of the world, as capitalism deeply shapes our values and practices. Capitalism has woven itself into our lives so extensively that most people have internalized its principles and ideologies. This internalization is evident in our daily choices, aspirations and perceptions of societal success and value, indicating how capitalism, as a total system, influences both economic exchanges and our worldview. It affects how we think about progress, how we relate to others and how we understand our roles within society. Beyond market transactions, capitalism extends into social, cultural and even personal and intimate areas of our lives.

Understanding and challenging capitalism

To critically examine and challenge capitalism, a foundational understanding of Marxist theory is essential. For designers, however, the topic of capitalism can be difficult to navigate due to misunderstood or obscured definitions and implications influenced by dominant cultural narratives. Capitalism’s appeal is often strengthened by mystification and cultural norms that obscure its systemic flaws and inequalities. Designers, often solution-focused and driven by innovation, may find it challenging to engage critically with capitalism as they prioritize novel solutions over deeper structural analysis. The allure of market-driven approaches and the belief in entrepreneurship as a vehicle for social change can overshadow the need for nuanced awareness of capitalism’s complexities and impacts.

Designers may also lack a precise framework for understanding capitalism, as public discourse on the topic is often oversimplified or clouded by ideological biases. This can lead to a superficial understanding, limiting designers’ ability to critically examine capitalism’s systemic effects and identify alternative approaches.

Capitalism as a mode of production

At its core, capitalism is a mode of production characterized by private ownership of the means of production—factories, land, machinery, social media, intellectual property, media outlets and logistics and supply chain networks. This system relies on exploiting labor power to generate surplus value. Grounded in profit maximization and accumulation, capitalism uses the means of production to produce commodities for sale at a profit. The extraction of surplus value from workers’ labor allows capitalists to accumulate wealth and expand their control over these means of production. This accumulation creates a class-based system in which capitalists, who own the means of production, dominate workers. Capitalism’s drive to innovate and increase productivity results in continuous growth and expansion, often at the expense of ecological sustainability and social well-being. Productivity gains are reinvested into production rather than promoting leisure or freedom for workers.

Neoliberalism’s impact on society and the state

Neoliberalism, an economic and political ideology, emphasizes the primacy of the market in organizing society while minimizing the state’s role in economic affairs. Neoliberalism promotes the privatization of public goods and services, deregulation and the dismantling of the welfare state. This results in a concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small elite, while most people face fewer protections and reduced access to healthcare, education and housing. Under neoliberalism, the state is restructured to facilitate capital accumulation by transnational corporations and global finance, often through mechanisms like tax breaks, subsidies and trade agreements that benefit the wealthy at the expense of workers, farmers and marginalized communities. Neoliberalism also emphasizes labor market “flexibility,” expecting workers to be mobile, adaptable and disposable to meet capital demands. This emphasis has led to the erosion of workers’ rights, increased precarious employment and a rise in low-wage jobs with few or no benefits.

Capitalism’s global infrastructure and its cultural influence

Capitalism depends on a global infrastructure deeply intertwined with political, economic and social systems. This infrastructure includes financial institutions, trade networks, technological platforms and legal frameworks reinforcing capitalist dynamics. Global governance structures often shaped by powerful capitalist actors support international organizations, trade agreements and financial systems that reinforce capitalism and limit space for alternative economic approaches. Technological advancements also support capitalism’s dominance, as technological platforms controlled by powerful corporations enable surveillance, data extraction and market control.

Capitalism also creates complex economic interdependencies across nations and regions, which makes it difficult for countries to challenge capitalist structures or deviate from the status quo without risking trade, investment and resource access disruptions. Capitalism fosters cultural norms that prioritize individualism, competition and profit-seeking, perpetuating inequality, reinforcing power imbalances and placing economic growth above social and environmental well-being. It sustains power imbalances between the Global North and South, where the North maintains dominance over the South. These dynamics stem from colonialism and neocolonial practices, which have historically exploited the South’s resources, labor and markets, resulting in ongoing economic and social inequalities.

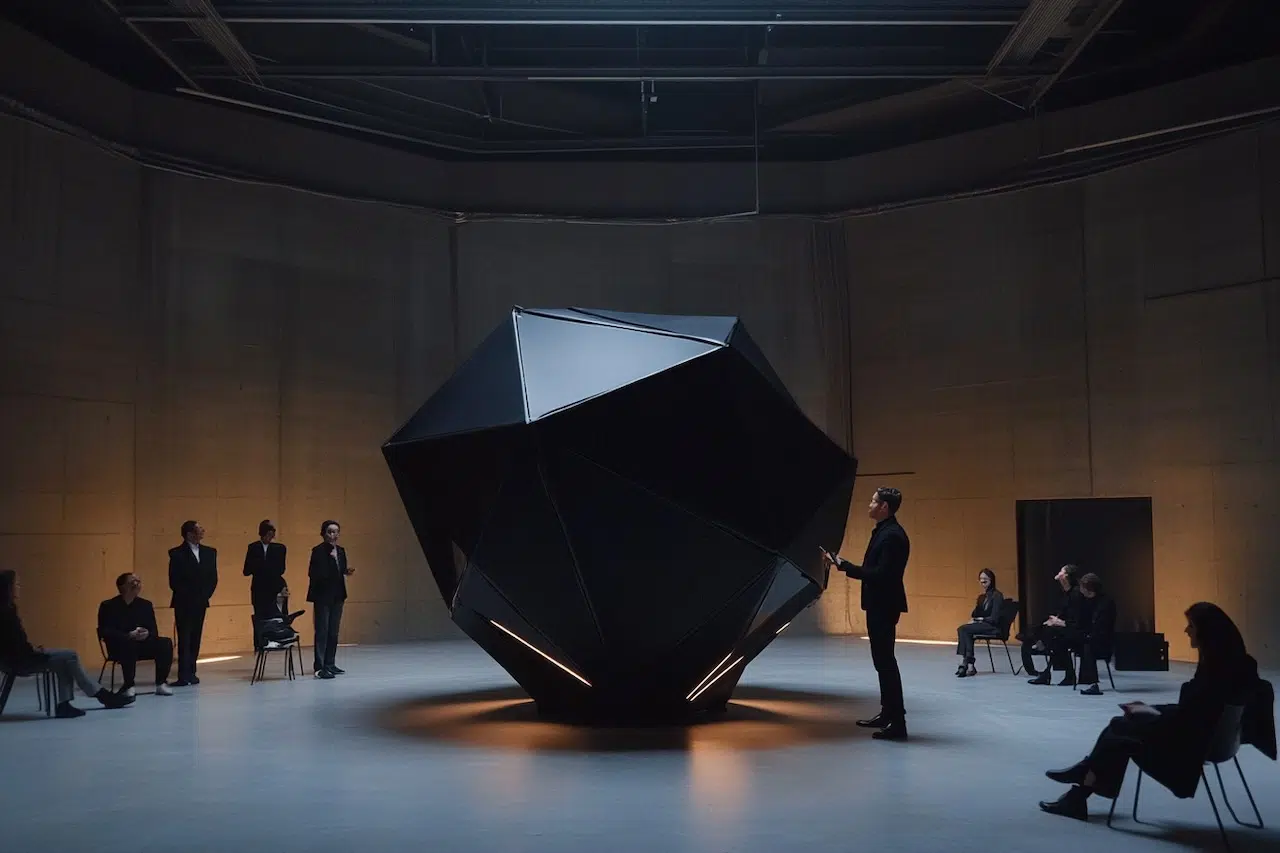

Visualizing capitalism’s reach and influence

Capitalism can be visualized as an octopus, with tentacles reaching into every aspect of our lives, representing different facets like corporations, financial institutions, advertising and consumer culture. Each tentacle reflects capitalism’s pervasive reach into economies, social systems and personal experiences, exerting control and shaping behavior. Another metaphor for capitalism is that of a grand theater production, where individuals play roles within the capitalist narrative on a stage that represents the economic landscape. Consumers, workers and entrepreneurs assume various roles within a system shaped by capitalist power dynamics. Alternatively, capitalism can be seen as a mental prison that limits imagination and traps thought patterns. Like prisoners in mental confinement, individuals under capitalism struggle to envision alternative futures, fostering resignation to capitalism’s dominance. Escaping this confinement requires critical consciousness, collective action and cultivating ideas that push beyond capitalist paradigms.

State and market relationships under capitalism and neoliberalism

In capitalism, the state plays a limited role in the economy while the market operates with considerable autonomy. Neoliberalism takes this further, with the state’s role minimized even more, leading to privatization of public goods, industry deregulation and reduced social protections. Both systems emphasize individual freedom and responsibility but interpret them differently.

Capitalism sees individual freedom as the pursuit of economic self-interest, while neoliberalism frames it as the ability to compete in the marketplace. In capitalism, individual responsibility involves generating wealth and contributing to economic growth; in neoliberalism, it involves self-reliance and limited dependence on state assistance.

Capitalism’s reinforcement of patriarchy and racial inequality

Aligned with conservative values, capitalism reinforces patriarchy by prioritizing traits typically associated with masculinity, like aggression and competitiveness, over those like collaboration and caregiving, traditionally associated with femininity. This devaluation of caregiving roles, often held by women, reinforces gendered hierarchies in the workplace. Structurally, capitalism relies on cheap labor, disproportionately affecting women and people of color, who are often paid lower wages and work in precarious positions.

Capitalism also perpetuates racism by sustaining inequality and discrimination that have existed for centuries. Scholars explore capitalism’s roots in practices like slavery, colonialism and imperialism, as well as the racial hierarchies created to justify these exploitations. Intersectional analysis recognizes that systems of oppression, like racism and capitalism, intersect and reinforce each other, shaping power dynamics and determining access to resources. Capitalism has historically relied on racialized labor, from colonial plantations to modern supply chains, marginalizing racial and ethnic groups through unequal conditions and wages.

The risks of capitalism in authoritarian regimes

When authoritarian leaders align with capitalist elites, democracy and human rights are often at risk. Under such regimes, democracy becomes a façade while real power remains concentrated in the hands of a few. This dynamic suppresses dissent and restricts freedoms, often justified as measures to preserve social stability and protect the economy. The rise of authoritarian regimes in countries like China and Russia, where capitalism coexists with authoritarianism, illustrates that capitalism does not guarantee democracy and can even reinforce authoritarian rule.

The role of plantations in capitalism’s development

Plantations played a critical role in capitalism’s development during the colonial era. These large-scale agricultural enterprises produced valuable commodities like sugar, tobacco, cotton and coffee for international trade, relying on enslaved or indentured labor. Scholars argue that plantations contributed to wealth accumulation in capitalist systems and to the global economic dominance of European powers. Plantations were also tied to colonialism and imperialism, facilitating unequal global power and resource distribution, with profits enriching capitalist centers while maintaining economic disparities and colonial control.

Extractivism and its environmental impact

Extractivism, particularly during the Anthropocene, reflects capitalism’s resource-exploitation model. It manifests unequal power dynamics between the Global North and South, perpetuating a colonial legacy of resource appropriation and economic dependence. Excessive resource extraction from the Global South to satisfy the North’s demands exacerbates social and environmental injustices. Extractivism accelerates ecological crises, including climate change and biodiversity loss, by disregarding ecological limits and pushing ecosystems beyond their resilience. Marginalized communities in the Global South bear the brunt of environmental degradation, land dispossession and livelihood erosion.

Digital capitalism and the commodification of personal data

Digital capitalism operates by framing labor as leisure within commercially oriented platforms. Users, seeking connection and access to digital services, engage with these platforms, often unaware that their activities constitute labor. By sharing preferences, creating content and interacting socially, users generate data that platform owners harvest, analyze and commodify. Smartphones have become tools for platforms to penetrate users’ private lives, enabling monetization of traditionally personal spaces. Surveillance marketing exploits this intrusion, breaching privacy under the pretense of freedom and connection, creating a narrative that entices users into leisure activities that mask data commodification.

Digital capitalism further mystifies itself by adopting language associated with communal and democratic values, concealing its commercial motivations. Phrases like “decentralization,” “sharing economy,” “social networking” and “tribal communities” create the illusion of egalitarian spaces with dispersed power, contrasting with capitalism’s traditional hierarchical model. These narratives make platforms seem more inclusive and less commercial, giving capitalism an aura of antagonism to its own structure. Yet beneath these narratives, capitalism’s mechanisms not only remain but are amplified.