The box is thinking you

They tell you to think outside the box like it’s a light switch you can flick. As if all it takes to break free is a little extra willpower, a brainstorm some sticky notes and voilà—innovation. But here’s the thing: if you don’t define the box first, it’s not just that you’re inside it. The box is thinking you. It’s shaping your perception, setting the rules and making sure you never even realize there’s a box in the first place.

The box isn’t a physical thing. It’s a construct of assumptions, constraints and narratives—most of them inherited some of them absorbed so deeply they’ve rewired your instincts. It’s mental models you never questioned, social structures you mistake for reality, default settings that define what you think is possible. You can’t think outside something you haven’t mapped. You can’t break free from what you haven’t even acknowledged is controlling you.

The architecture of the box

The box is built out of sense-making gone stale. It’s constructed from overused narratives, lazy problem framings and borrowed logic from whatever industrial-age institution originally set the terms of engagement. It’s every “best practice” that stops you from questioning why that practice exists in the first place. It’s the algorithm that keeps serving you up the same five solutions to problems you never really examined.

And yet designers keep trying to solve things inside the damn thing. Take a problem, run it through a process and out pops the same predictable pre-approved answer. A slightly more sustainable version of the same broken system. A marginally more ethical design for a world that’s already two decades past its warranty date. Without defining the box, without pushing at the edges, all you’re doing is iterating inside your cage.

Sense-making is supposed to break this loop. It’s the process of actually figuring out where you are what’s shaping your perspective and why things look the way they do. But even sense-making can get hijacked by the same stale thinking. The moment it stops being disruptive it becomes just another self-referential feedback loop. Mapping the system isn’t enough if you’re just coloring inside the lines.

How the box makes sure you never see it

The best trick the box ever pulled was convincing you that it doesn’t exist. That your understanding of a problem is natural. That the way things are framed is neutral. That certain solutions are just “common sense.”

Except of course common sense is just the sum total of collective blind spots. And the people who set the definitions—the ones who wrote the original problem statements, designed the original frameworks and enforced the original categories—were not exactly neutral parties. They were maintaining something. And if you don’t interrogate that if you don’t ask who benefits from this framing? then congratulations: you’re not thinking outside the box, you’re just thinking like a well-behaved product of it.

Reframing is the only way out but reframing is war. You’re not just nudging a few words around. You’re challenging the foundation. You’re asking questions that make people uncomfortable because they should be uncomfortable. When you redefine a problem, you’re messing with power structures with business models with deep-seated narratives. You’re making the implicit explicit and trust me people hate that.

The escape vector

So what now? Well first understand that you’re never fully outside the box. That’s another trick. You don’t escape it once and call it a day. The moment you think you’re free you’ve probably just stepped into a more sophisticated version of the same trap.

What you do is keep moving. Keep defining redefining questioning. Keep making maps and then burning them when they start looking too familiar. Treat every framing as a temporary tool not a permanent structure. Take the problem twist it sideways turn it upside down ask how it looks from the perspective of someone with nothing to lose. Stop assuming that the first clear solution is the right one—it’s probably just the most convenient one.

And for the love of all things messy and interesting stop worshiping efficiency. The box loves efficiency. It thrives on it. Efficiency is just calcified thinking the smooth seamless repetition of the same. Instead embrace friction. Hunt for the weird edges. Notice what doesn’t fit. That’s usually where the real work begins.

Because in the end thinking outside the box isn’t about ideas. It’s about seeing the box for what it is and then making damn sure it doesn’t think for you.

Appendix: a post-Cold War expression

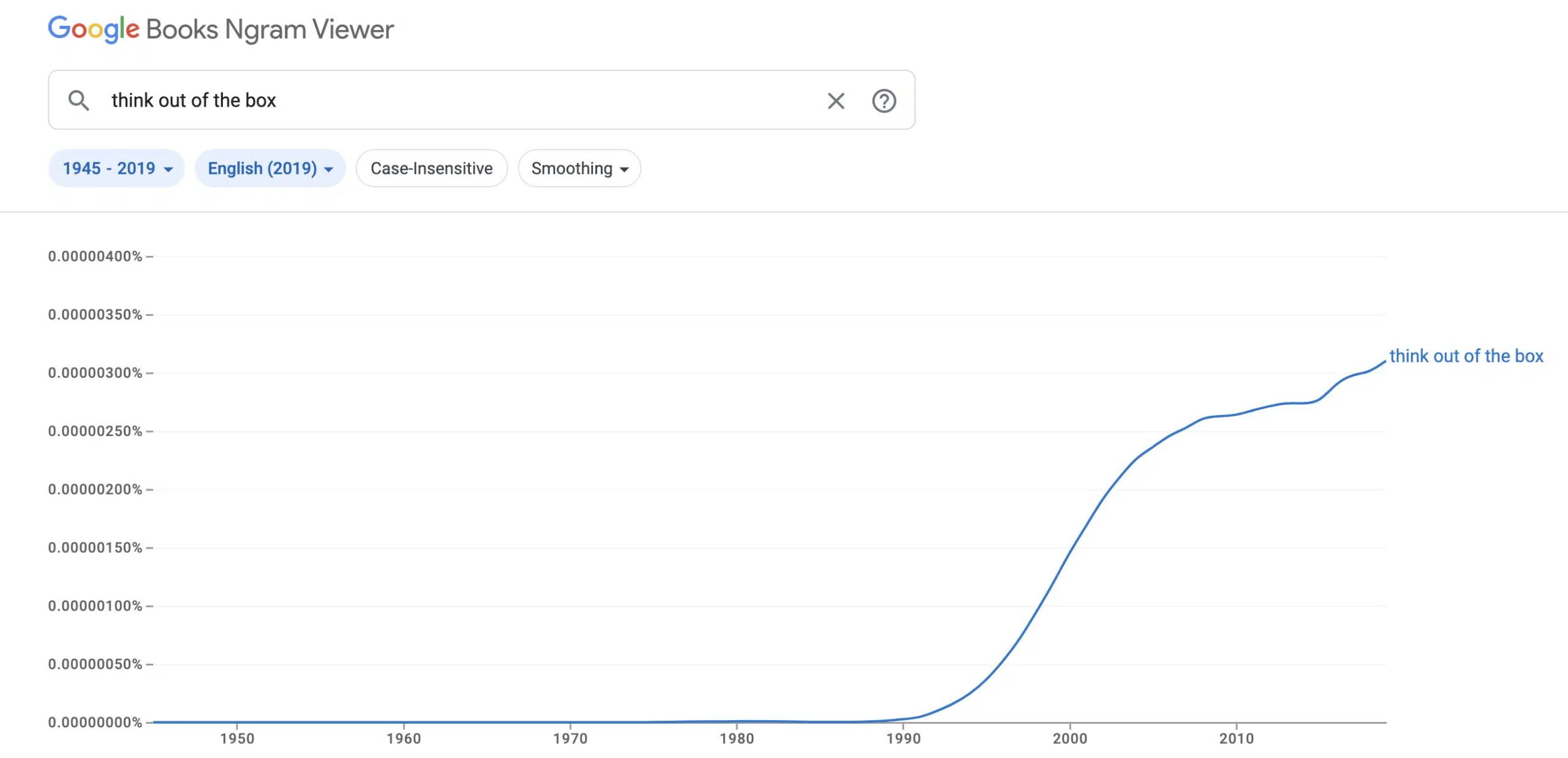

Source: Ngarm Viewer – The Google Ngram Viewer is a tool that allows users to search and analyze the frequency of words and phrases in a large database of books.

It is difficult to say exactly why the phrase “think out of the box” appears to have grown in popularity after the end of the Cold War, as there are likely a number of factors at play.

One possible explanation is that the end of the Cold War marked a significant shift in global politics and economic systems, and this shift may have led to a greater emphasis on innovation and creative thinking as businesses and organizations sought to adapt to new realities. In this context, the phrase “think out of the box” may have gained popularity as a way to encourage people to embrace new ideas and approaches and to challenge conventional wisdom.

The phrase “think outside the box” is also often associated with the “nine dots” puzzle, which is a problem that requires people to think creatively in order to find a solution. The puzzle which started to grow in popularity during the 80s consists of nine dots arranged in a three-by-three grid, and the goal is to draw four straight lines that connect all of the dots without lifting the pen from the paper. Then the participants would be required to connect the dots using only three, requiring to play with the problem creatively.